I’m often asked how I communicate with the tribe. Answer: “it’s not easy!” It was particularly difficult in the beginning, before I knew any Amharic or Hamar.

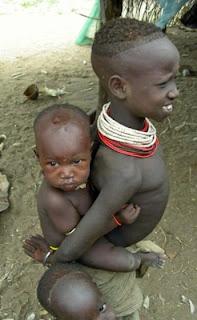

My first extended stay in “Hamar-land” was February to April 2008 when we conducted our comprehensive needs analysis. Our program called for us to visit 10 Hamar kebeles (small counties) and interview elders, men, women, health workers, and others, with a series of open-ended questions that we hoped would identify the barriers between the Hamar and a healthy life.

Good plan. . . Tough to implement!

I was traveling with an English/Amharic translator, or so I was promised. Damtew was top of his university class in English communication, which meant he could read English – which is not the same as understanding a native English speaker! Fortunately, Fekade, our driver, could also speak some English. But neither of them spoke the tribal Hamar language. So in Turmi, the nearest town, we picked up Enyite – “the best Hamar/Amharic translator available.”

The interview process went like this:

Lori asks question in English

Damtew, Fekade and Enyite discuss the question for 10 minutes in Amharic

Enyite asks the question in Hamar – which takes 5 minutes

Hamar interviewee responds in three words

Enyite yells the question in Hamar – another 5 minutes

Hamar interviewee stutters his or her response

Enyite, Damtew and Fekade discuss the response in Amharic

Enyite says something in Hamar

Hamar interviewee clams up, seemingly afraid to respond

Enyite yells

Hamar mutters a response

Enyite, Damtew and Fekade speak Amharic

Damtew gives me the answer to a question I did not ask!

It took us 45 days to gather all the information – time in which I received the gift of a lifetime. Forced to be quiet, to listen, to observe body language, I learned simply “to be.”

And by sitting still, showing up day after day, proving that we really cared about what they thought, we laid a foundation of trust between the Hamar and ourselves.